Data Encoding and Transmission- Part 2 of Designing Data-Intensive Applications

This blog talks about various data encoding methods and their advantages/limitations, along with protocols of transmitting them.

Efficiency is certainly one of the main concerns for various encoding methods. The other thing we need to care about is compatibility. Backward compatibility means that newer code can read data that was written by older code. and Forward compatibility means that older code can read data that was written by newer code. Backward compatibility is normally not hard to achieve: as author of the newer code, you know the format of data written by older code, and so you can explicitly handle it (if necessary by simply keeping the old code to read the old data). Forward compatibility can be trickier, because it requires older code to ignore additions made by a newer version of the code.

Programming language–specific encodingsPermalink

Examples java.io.Serializable for Java, pickle for Python. Problems:

- The encoding is often tied to a particular programming language, and reading the data in another language is very difficult. If you store or transmit data in such an encoding, you are committing yourself to your current programming language for potentially a very long time, and precluding integrating your systems with those of other organizations (which may use different languages).

- In order to restore data in the same object types, the decoding process needs to be able to instantiate arbitrary classes. This is frequently a source of security problems: if an attacker can get your application to decode an arbitrary byte sequence, they can instantiate arbitrary classes, which in turn often allows them to do terrible things such as remotely executing arbitrary code.

- Versioning data is often an afterthought in these libraries: as they are intended for quick and easy encoding of data, they often neglect the inconvenient problems of forward and backward compatibility.

- Efficiency (CPU time taken to encode or decode, and the size of the encoded structure) is also often an afterthought. For example, Java’s built-in serialization is notorious for its bad performance and bloated encoding.

For these reasons it’s generally a bad idea to use your language’s built-in encoding for anything other than very transient purpose

JSON, XML, and Binary VariantsPermalink

Problems:

- There is a lot of ambiguity around the encoding of numbers. In XML and CSV, you cannot distinguish between a number and a string that happens to consist of digits (except by referring to an external schema). JSON distinguishes strings and numbers, but it doesn’t distinguish integers and floating-point numbers, and it doesn’t specify a precision. This is a problem when dealing with large numbers; for example, integers greater than 253 cannot be exactly represented in an IEEE 754 double-precision floating- point number, so such numbers become inaccurate when parsed in a language that uses floating-point numbers (such as JavaScript). An example of numbers larger than 253 occurs on Twitter, which uses a 64-bit number to identify each tweet. The JSON returned by Twitter’s API includes tweet IDs twice, once as a JSON number and once as a decimal string, to work around the fact that the numbers are not correctly parsed by JavaScript applications.

- JSON and XML have good support for Unicode character strings (i.e., human-readable text), but they don’t support binary strings (sequences of bytes without a character encoding). Binary strings are a useful feature, so people get around this limitation by encoding the binary data as text using Base64. The schema is then used to indicate that the value should be interpreted as Base64-encoded. This works, but it’s somewhat hacky and increases the data size by 33%.

- CSV does not have any schema, so it is up to the application to define the meaning of each row and column. If an application change adds a new row or column, you have to handle that change manually. CSV is also a quite vague format (what happens if a value contains a comma or a newline character?). Although its escaping rules have been formally specified, not all parsers implement them correctly.

Despite these flaws, JSON, XML, and CSV are good enough for many purposes. It’s likely that they will remain popular, especially as data interchange formats (i.e., for sending data from one organization to another). In these situations, as long as people agree on what the format is, it often doesn’t matter how pretty or efficient the format is. The difficulty of getting different organizations to agree on anything outweighs most other concerns.

Binary EncodingPermalink

MessagePackPermalink

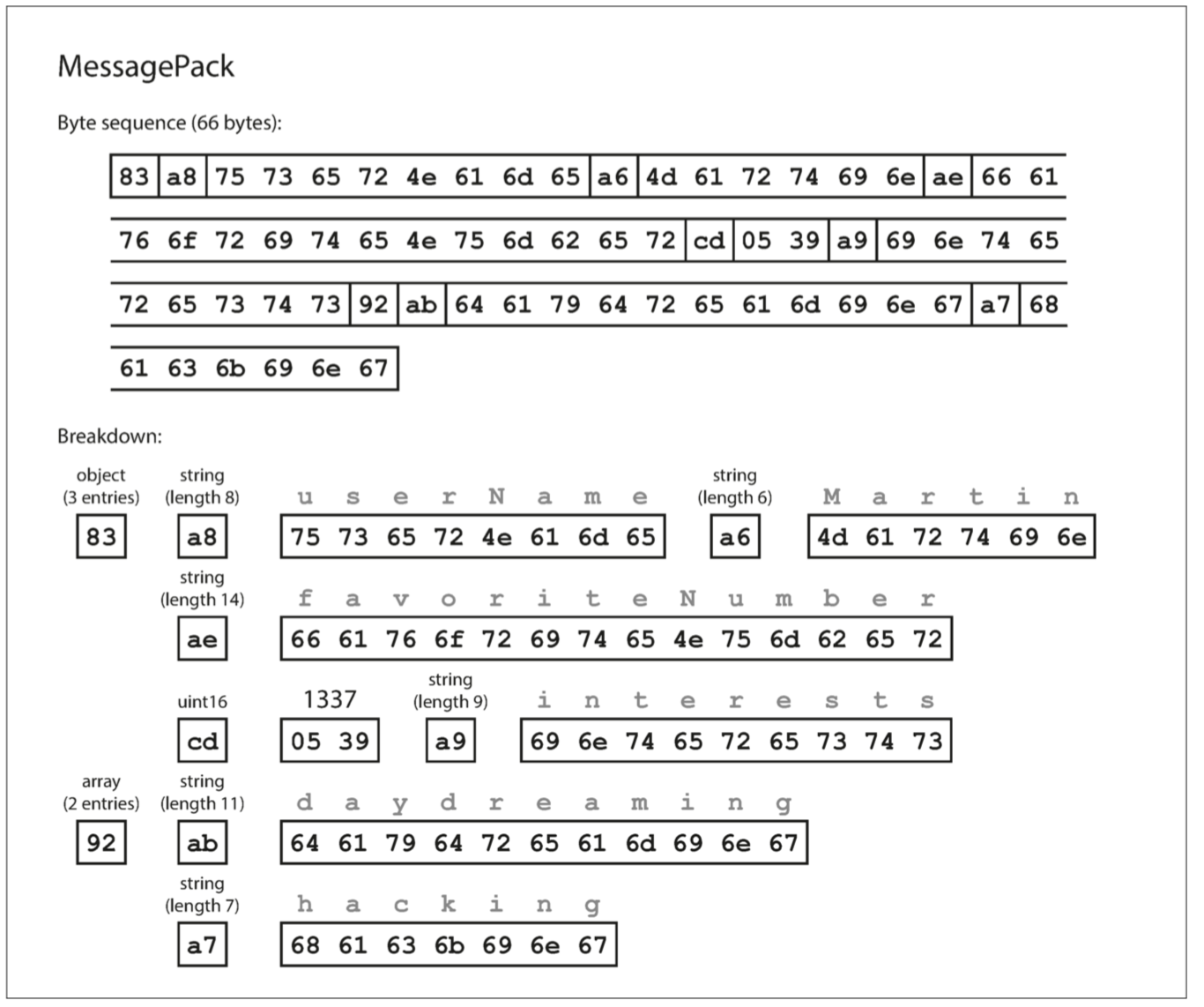

MessagePack is a binary encoding for JSON. Here is an example:

- The first byte, 0x83, indicates that what follows is an object (top four bits = 0x80) with three fields (bottom four bits = 0x03). (In case you’re wondering what happens if an object has more than 15 fields, so that the number of fields doesn’t fit in four bits, it then gets a different type indicator, and the number of fields is encoded in two or four bytes.)

- The second byte, 0xa8, indicates that what follows is a string (top four bits = 0xa0) that is eight bytes long (bottom four bits = 0x08).

- The next eight bytes are the field name “userName” in ASCII. Since the length was indicated previously, there’s no need for any marker to tell us where the string ends (or any escaping).

- The next seven bytes encode the six-letter string value Martin with a prefix 0xa6, and so on.

The binary encoding is 66 bytes long, which is only a little less than the 81 bytes taken by the textual JSON encoding (with whitespace removed). All the binary encodings of JSON are similar in this regard. It’s not clear whether such a small space reduction (and perhaps a speedup in parsing) is worth the loss of human-readability.

Thrift and Protocol BuffersPermalink

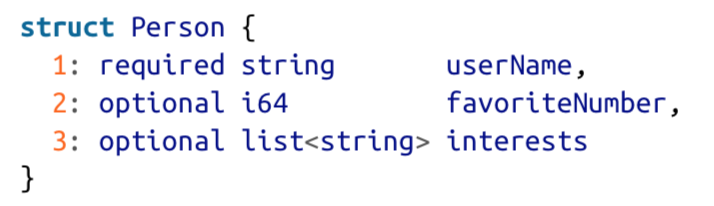

Apache Thrift and Protocol Buffers (protobuf) are binary encoding libraries that are based on the same principle. Protocol Buffers was originally developed at Google, Thrift was originally developed at Facebook, and both were made open source in 2007–08.

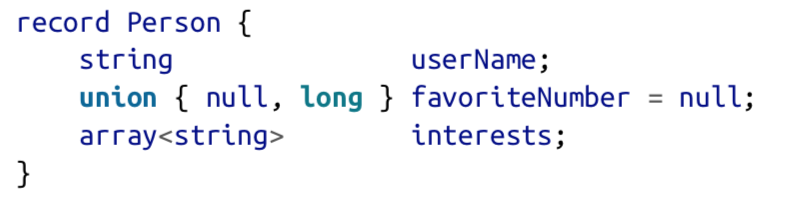

Both Thrift and Protocol Buffers require a schema for any data that is encoded. To encode the data above in Thrift, you would describe the schema in the Thrift interface definition language (IDL) like this:

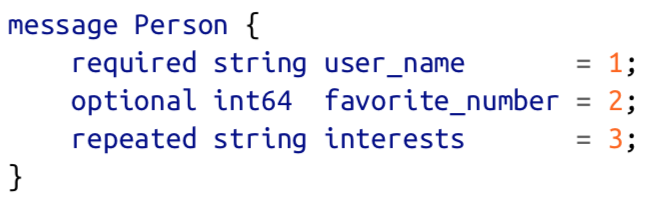

The equivalent schema definition for Protocol Buffers looks very similar:

Thrift and Protocol Buffers each come with a code generation tool that takes a schema definition like the ones shown here, and produces classes that implement the schema in various programming languages. Your application code can call this generated code to encode or decode records of the schema.

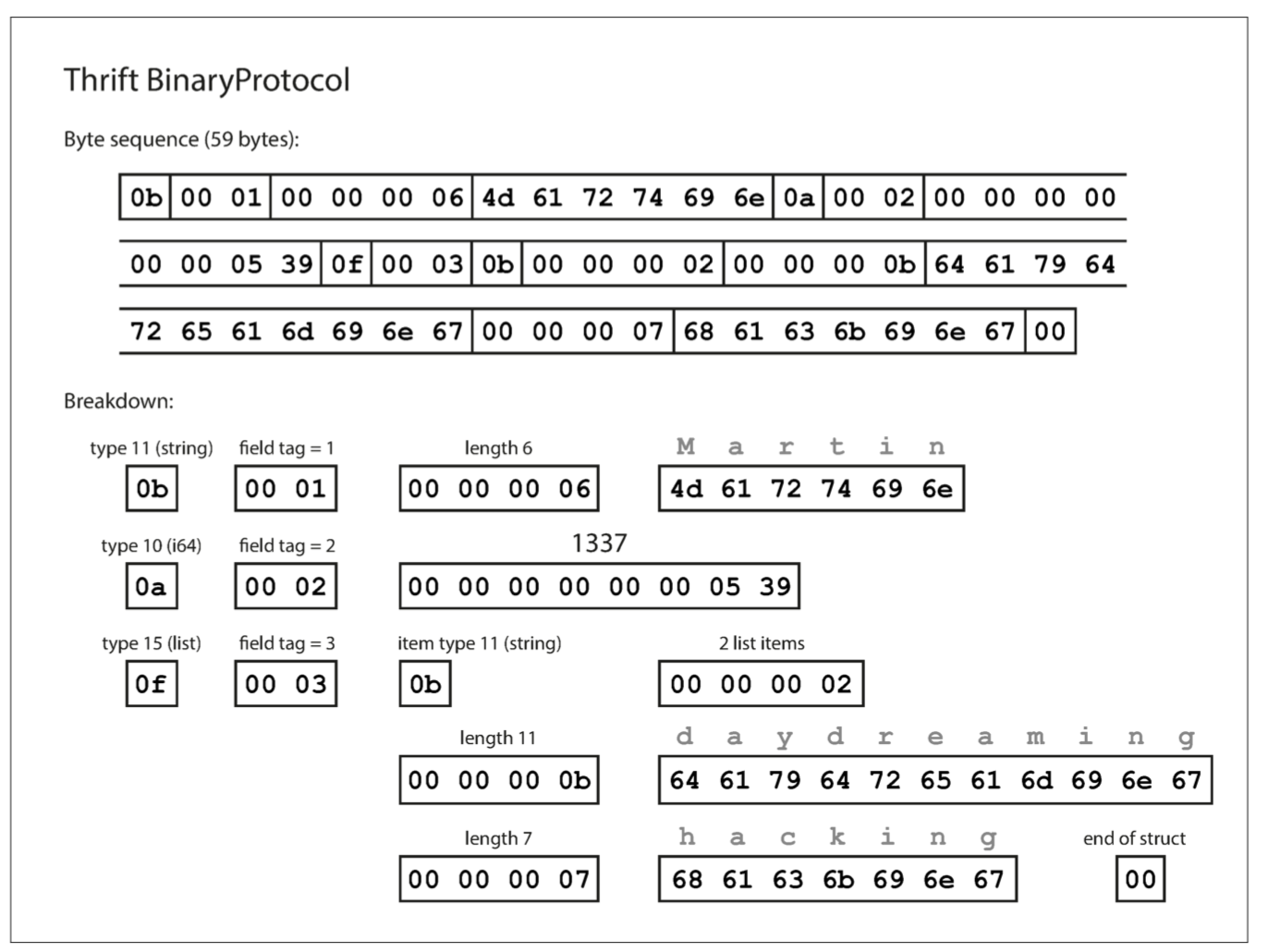

Confusingly, Thrift has two different binary encoding formats, called BinaryProtocol and CompactProtocol, respectively. Let’s look at BinaryProtocol first.

Similarly to MessagePack, each field has a type annotation (to indicate whether it is a string, integer, list, etc.) and, where required, a length indication (length of a string, number of items in a list). The strings that appear in the data (“Martin”, “daydreaming”, “hacking”) are also encoded as ASCII (or rather, UTF-8), similar to before.

The big difference compared to MessagePack is that there are no field names (userName, favoriteNumber, interests). Instead, the encoded data contains field tags, which are numbers (1, 2, and 3). Those are the numbers that appear in the schema definition. Field tags are like aliases for fields—they are a compact way of saying what field we’re talking about, without having to spell out the field name.

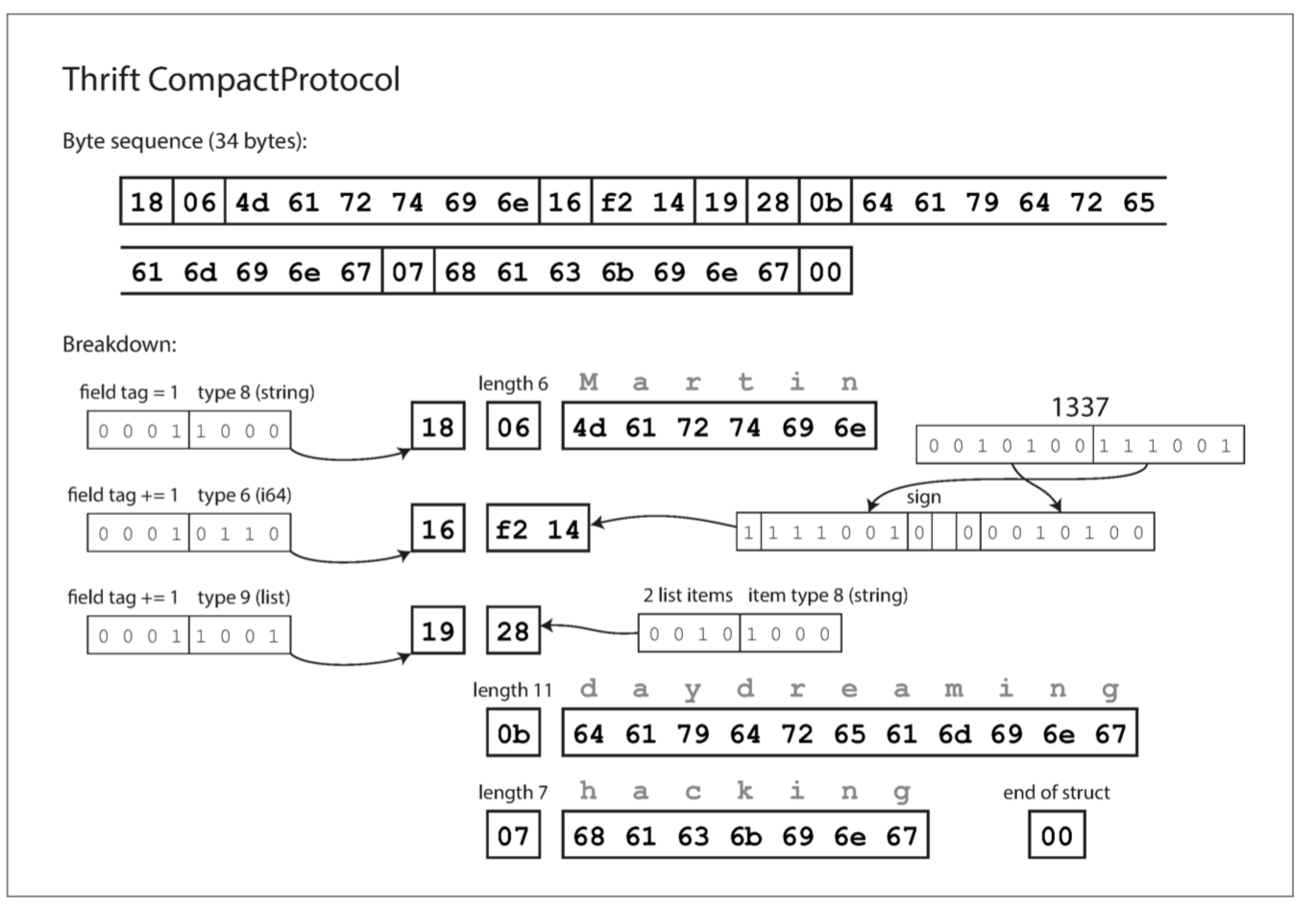

The Thrift CompactProtocol encoding is semantically equivalent to BinaryProtocol, but as you can see in the following, it packs the same information into only 34 bytes. It does this by packing the field type and tag number into a single byte, and by using variable-length integers. Rather than using a full eight bytes for the number 1337, it is encoded in two bytes, with the top bit of each byte used to indicate whether there are still more bytes to come. This means numbers between –64 and 63 are encoded in one byte, numbers between –8192 and 8191 are encoded in two bytes, etc. Bigger numbers use more bytes.

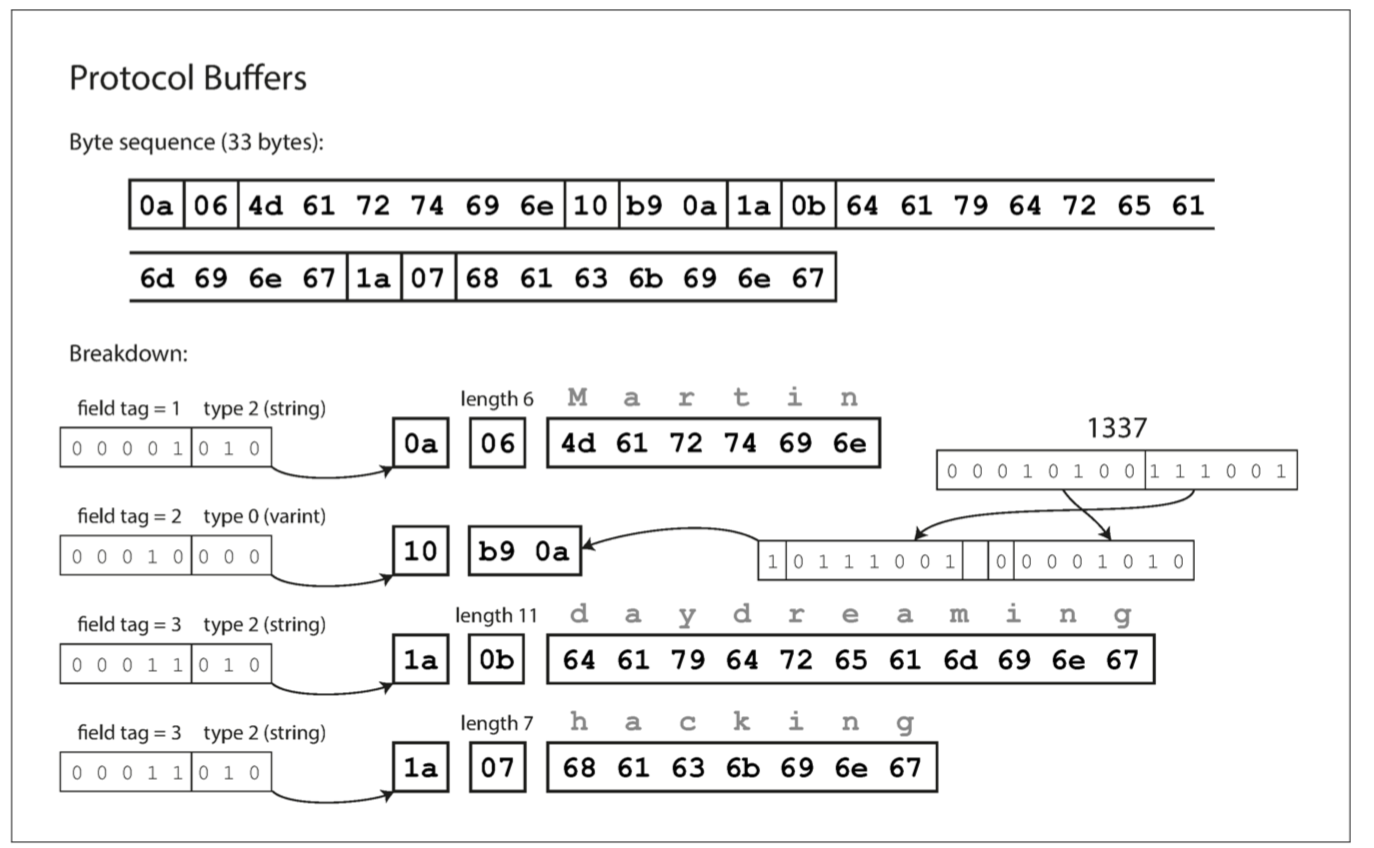

Finally, Protocol Buffers (which has only one binary encoding format) encodes the same data as shown in Figure 4-4. It does the bit packing slightly differently, but is otherwise very similar to Thrift’s CompactProtocol. Protocol Buffers fits the same record in 33 bytes.

CompatibilityPermalink

For forward compatibility, You can change the name of a field in the schema, since the encoded data never refers to field names, but you cannot change a field’s tag, since that would make all existing encoded data invalid. You can add new fields to the schema, provided that you give each field a new tag number. If old code (which doesn’t know about the new tag numbers you added) tries to read data written by new code, including a new field with a tag number it doesn’t recognize, it can simply ignore that field. The datatype annotation allows the parser to determine how many bytes it needs to skip. This maintains forward compatibility: old code can read records that were written by new code.

For backward compatibility, As long as each field has a unique tag number, new code can always read old data, because the tag numbers still have the same meaning. The only detail is that if you add a new field, you cannot make it required. If you were to add a field and make it required, that check would fail if new code read data written by old code, because the old code will not have written the new field that you added. Therefore, to maintain backward compatibility, every field you add after the initial deployment of the schema must be optional or have a default value.

Removing a field is just like adding a field, with backward and forward compatibility concerns reversed. That means you can only remove a field that is optional (a required field can never be removed), and you can never use the same tag number again (because you may still have data written somewhere that includes the old tag number, and that field must be ignored by new code).

Changing datatype of a field is possible, but there’s a risk that values will lose precision or get truncated (say if you write a 64-bit variable and decode it in 32 bits).

AvroPermalink

Apache Avro is another binary encoding format that is interestingly different from Protocol Buffers and Thrift. It was started in 2009 as a subproject of Hadoop, as a result of Thrift not being a good fit for Hadoop’s use cases.

Avro also uses a schema to specify the structure of the data being encoded. It has two schema languages: one (Avro IDL) intended for human editing, and one (based on JSON) that is more easily machine-readable.

Our example schema, written in Avro IDL, might look like this:

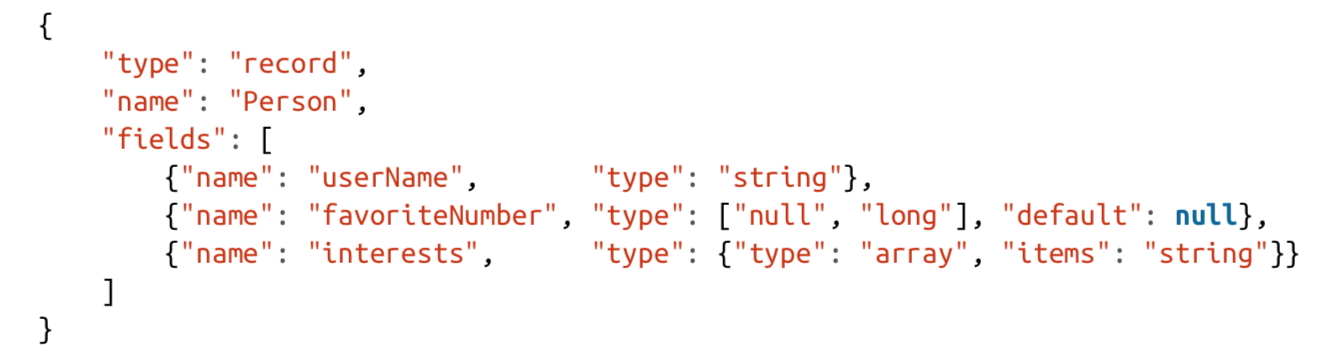

The equivalent JSON representation of that schema is as follows:

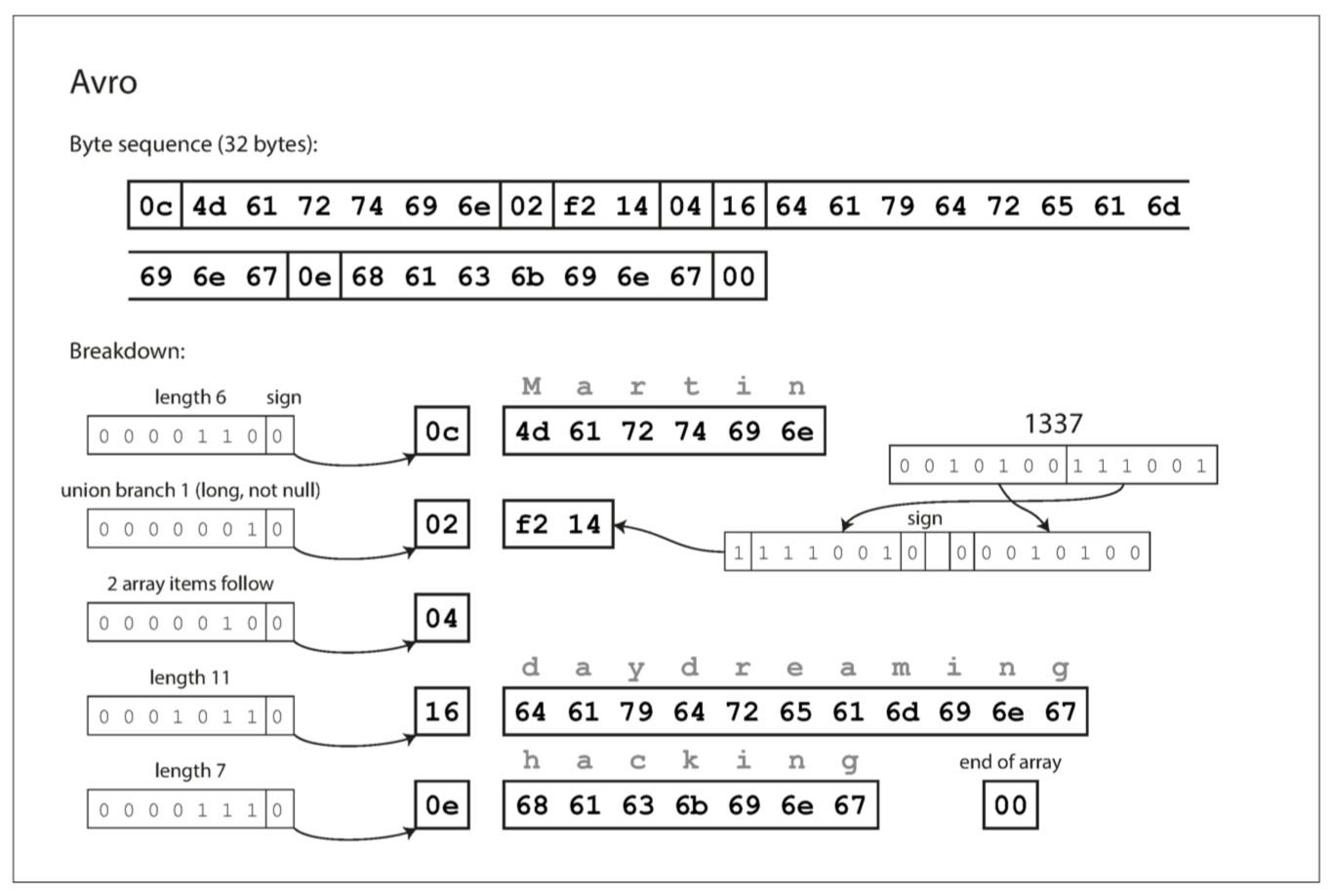

Here is the breakdown of the encoded byte sequence:

First of all, notice that there are no tag numbers in the schema.

If you examine the byte sequence, you can see that there is nothing to identify fields or their datatypes. The encoding simply consists of values concatenated together. A string is just a length prefix followed by UTF-8 bytes, but there’s nothing in the encoded data that tells you that it is a string. It could just as well be an integer, or something else entirely. An integer is encoded using a variable-length encoding (the same as Thrift’s CompactProtocol).

To parse the binary data, you go through the fields in the order that they appear in the schema and use the schema to tell you the datatype of each field. This means that the binary data can only be decoded correctly if the code reading the data is using the exact same schema as the code that wrote the data. Any mismatch in the schema between the reader and the writer would mean incorrectly decoded data.

CompatibilityPermalink

With Avro, when an application wants to encode some data (to write it to a file or database, to send it over the network, etc.), it encodes the data using whatever version of the schema it knows about—for example, that schema may be compiled into the application. This is known as the writer’s schema.

When an application wants to decode some data (read it from a file or database, receive it from the network, etc.), it is expecting the data to be in some schema, which is known as the reader’s schema. That is the schema the application code is relying on -code may have been generated from that schema during the application’s build process.

The key idea with Avro is that the writer’s schema and the reader’s schema don’t have to be the same—they only need to be compatible. When data is decoded (read), the Avro library resolves the differences by looking at the writer’s schema and the reader’s schema side by side and translating the data from the writer’s schema into the reader’s schema. The Avro specification defines exactly how this resolution works, and it is illustrated below.

For example, it’s no problem if the writer’s schema and the reader’s schema have their fields in a different order, because the schema resolution matches up the fields by field name. If the code reading the data encounters a field that appears in the writer’s schema but not in the reader’s schema, it is ignored. If the code reading the data expects some field, but the writer’s schema does not contain a field of that name, it is filled in with a default value declared in the reader’s schema.

With Avro, forward compatibility means that you can have a new version of the schema as writer and an old version of the schema as reader. Conversely, backward compatibility means that you can have a new version of the schema as reader and an old version as writer.

To maintain compatibility, you may only add or remove a field that has a default value. (The field favoriteNumber in our Avro schema has a default value of null.) For example, say you add a field with a default value, so this new field exists in the new schema but not the old one. When a reader using the new schema reads a record written with the old schema, the default value is filled in for the missing field.

If you were to add a field that has no default value, new readers wouldn’t be able to read data written by old writers, so you would break backward compatibility. If you were to remove a field that has no default value, old readers wouldn’t be able to read data written by new writers, so you would break forward compatibility.

Writer’s SchemaPermalink

There is an important question that we’ve glossed over so far: how does the reader know the writer’s schema with which a particular piece of data was encoded? We can’t just include the entire schema with every record, because the schema would likely be much bigger than the encoded data, making all the space savings from the binary encoding futile.

The answer depends on the context in which Avro is being used. To give a few examples:

- Large file with lots of records: A common use for Avro—especially in the context of Hadoop—is for storing a large file containing millions of records, all encoded with the same schema. In this case, the writer of that file can just include the writer’s schema once at the beginning of the file. Avro specifies a file format (object container files) to do this.

- Database with individually written records: In a database, different records may be written at different points in time using different writer’s schemas—you cannot assume that all the records will have the same schema. The simplest solution is to include a version number at the beginning of every encoded record, and to keep a list of schema versions in your database. A reader can fetch a record, extract the version number, and then fetch the writer’s schema for that version number from the database. Using that writer’s schema, it can decode the rest of the record. (Espresso works this way, for example.)

- Sending records over a network connection: When two processes are communicating over a bidirectional network connec‐ tion, they can negotiate the schema version on connection setup and then use that schema for the lifetime of the connection. The Avro RPC protocol works like this.

Dynamically generated SchemasPermalink

One advantage of Avro’s approach, compared to Protocol Buffers and Thrift, is that the schema doesn’t contain any tag numbers. But why is this important? What’s the problem with keeping a couple of numbers in the schema?

The difference is that Avro is friendlier to dynamically generated schemas. For example, say you have a relational database whose contents you want to dump to a file, and you want to use a binary format to avoid the aforementioned problems with textual formats (JSON, CSV, SQL). If you use Avro, you can fairly easily generate an Avro schema (in the JSON representation we saw earlier) from the relational schema and encode the database contents using that schema, dumping it all to an Avro object container file. You generate a record schema for each database table, and each column becomes a field in that record. The column name in the database maps to the field name in Avro.

Now, if the database schema changes (for example, a table has one column added and one column removed), you can just generate a new Avro schema from the updated database schema and export data in the new Avro schema. The data export process does not need to pay any attention to the schema change—it can simply do the schema conversion every time it runs. Anyone who reads the new data files will see that the fields of the record have changed, but since the fields are identified by name, the updated writer’s schema can still be matched up with the old reader’s schema.

By contrast, if you were using Thrift or Protocol Buffers for this purpose, the field tags would likely have to be assigned by hand: every time the database schema changes, an administrator would have to manually update the mapping from data‐ base column names to field tags. (It might be possible to automate this, but the schema generator would have to be very careful to not assign previously used field tags.) This kind of dynamically generated schema simply wasn’t a design goal of Thrift or Protocol Buffers, whereas it was for Avro.

Code Generation and Dynamically Typed LanguagesPermalink

Thrift and Protocol Buffers rely on code generation: after a schema has been defined, you can generate code that implements this schema in a programming language of your choice. This is useful in statically typed languages such as Java, C++, or C#, because it allows efficient in-memory structures to be used for decoded data, and it allows type checking and autocompletion in IDEs when writing programs that access the data structures.

In dynamically typed programming languages such as JavaScript, Ruby, or Python, there is not much point in generating code, since there is no compile-time type checker to satisfy. Code generation is often frowned upon in these languages, since they otherwise avoid an explicit compilation step. Moreover, in the case of a dynamically generated schema (such as an Avro schema generated from a database table), code generation is an unnecessarily obstacle to getting to the data.

Avro provides optional code generation for statically typed programming languages, but it can be used just as well without any code generation. If you have an object container file (which embeds the writer’s schema), you can simply open it using the Avro library and look at the data in the same way as you could look at a JSON file. The file is self-describing since it includes all the necessary metadata.

This property is especially useful in conjunction with dynamically typed data processing languages like Apache Pig [26]. In Pig, you can just open some Avro files, start analyzing them, and write derived datasets to output files in Avro format without even thinking about schemas.

Models of DataflowPermalink

Dataflow Through DatabasesPermalink

In a database, the process that writes to the database encodes the data, and the process that reads from the database decodes it. There may just be a single process accessing the database, in which case the reader is simply a later version of the same process—in that case you can think of storing something in the database as sending a message to your future self.

A couple issues need to be taken care of:

A database generally allows any value to be updated at any time. This means that within a single database you may have some values that were written five milliseconds ago, and some values that were written five years ago.

When you deploy a new version of your application (of a server-side application, at least), you may entirely replace the old version with the new version within a few minutes. The same is not true of database contents: the five-year-old data will still be there, in the original encoding, unless you have explicitly rewritten it since then. This observation is sometimes summed up as data outlives code.

Rewriting (migrating) data into a new schema is certainly possible, but it’s an expensive thing to do on a large dataset, so most databases avoid it if possible. Most relational databases allow simple schema changes, such as adding a new column with a null default value, without rewriting existing data.v When an old row is read, the database fills in nulls for any columns that are missing from the encoded data on disk. LinkedIn’s document database Espresso uses Avro for storage, allowing it to use Avro’s schema evolution rules.

Schema evolution thus allows the entire database to appear as if it was encoded with a single schema, even though the underlying storage may contain records encoded with various historical versions of the schema.

Dataflow Through Services: REST and RPCPermalink

We all know about REST and RPC so we’ll just talk about the relationships between them and data encoding, i.e. compatibility.

For evolvability, it is important that RPC clients and servers can be changed and deployed independently. Compared to data flowing through databases (as described in the last section), we can make a simplifying assumption in the case of dataflow through services: it is reasonable to assume that all the servers will be updated first, and all the clients second. Thus, you only need backward compatibility on requests, and forward compatibility on responses. And bhe backward and forward compatibility properties of an RPC scheme are inherited from whatever encoding it uses.

Message-Passing DataflowPermalink

Basically a streaming or pub/sub system like RabbitMQ and Kafka.

Comments